Research

Our lab focuses on computational biology and cancer research. We analyze large genomics and other -omics datasets of various cancer types using statistical and machine learning approaches. We alo develop new methods to ask unique questions on the data. We occasionally perform functional experiments in close collaborations with experimental labs to validate our most promising findings. Research in the lab falls under three broad themes.

Drivers & passengers of the cancer genome

Cancer is a genetic disease caused by somatic mutations in the genome. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and other classes of mutations accumulate in the genome over time and through exposures to DNA-damaging agents. Most mutations have little consequence and are often called passengers, while a small minority of mutations called drivers affect critical genes in cells and cause aberrant activity of oncogenic and tumor suppresive pathways in cells.

Recent research in the lab has focused on both drivers and passengers in large whole-genome sequencing datasets.

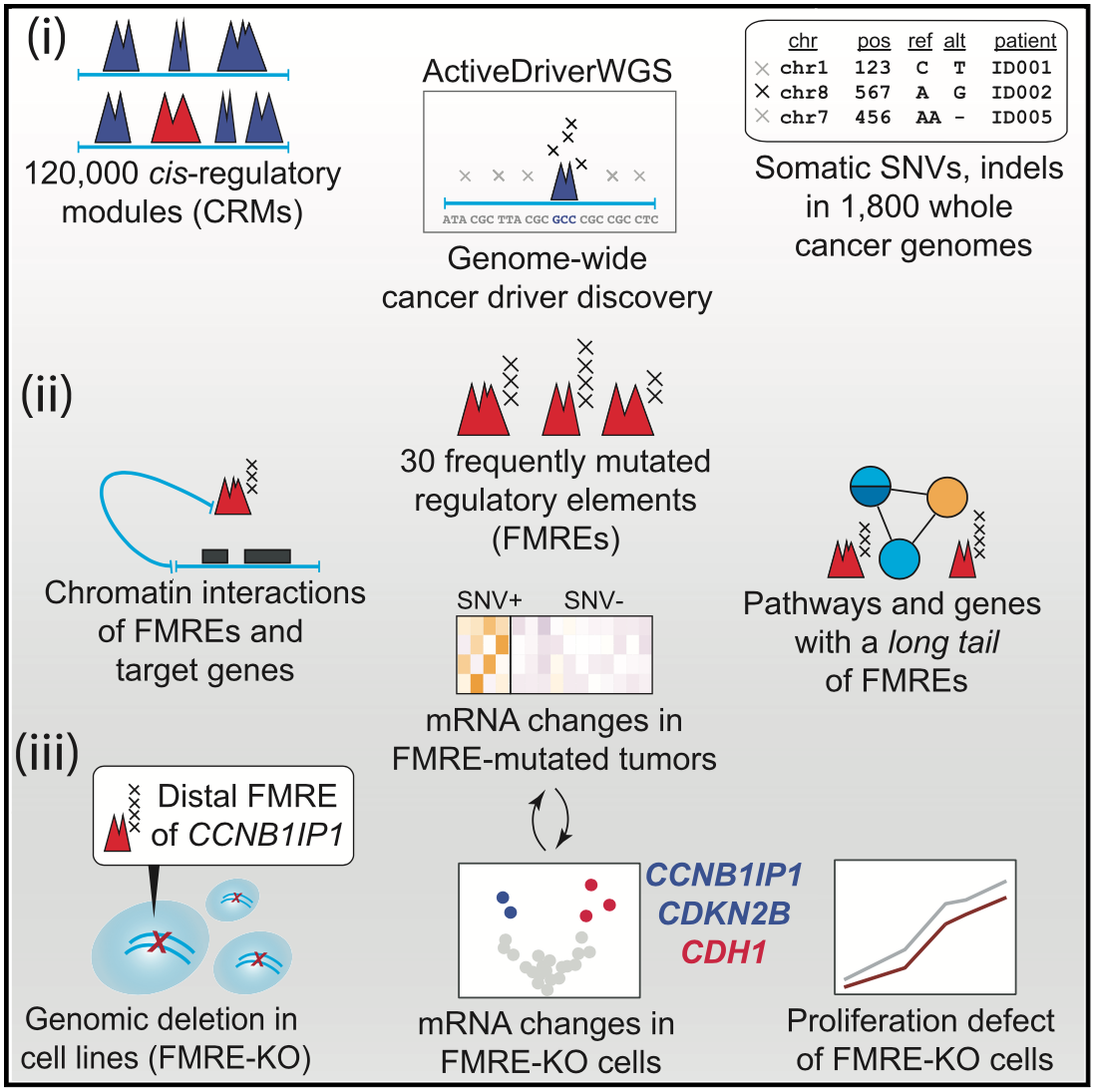

For driver mutations, we recently performed a systematic analysis of potential non-coding drivers in gene-regulatory regions and three-dimensional interaction hubs of the cancer genome using cancer whole-genome sequencing data. We found dozens of potential novel driver mutations and performed functional experiments with CRISPR genome editing and transcriptome-wide profiling to validate one non-coding region controlling the tumor suppressor gene CCNB1IP1. We developed the computational tool ActiveDriverWGS to enable such discovery.

Candidate cancer driver mutations in distal regulatory elements and long-range chromatin interaction networks.

Helen Zhu*, Liis Uusküla-Reimand*, Keren Isaev*, .. , Jüri Reimand.

Molecular Cell 77 (6) 1307-1321. e10 (2020)

link.

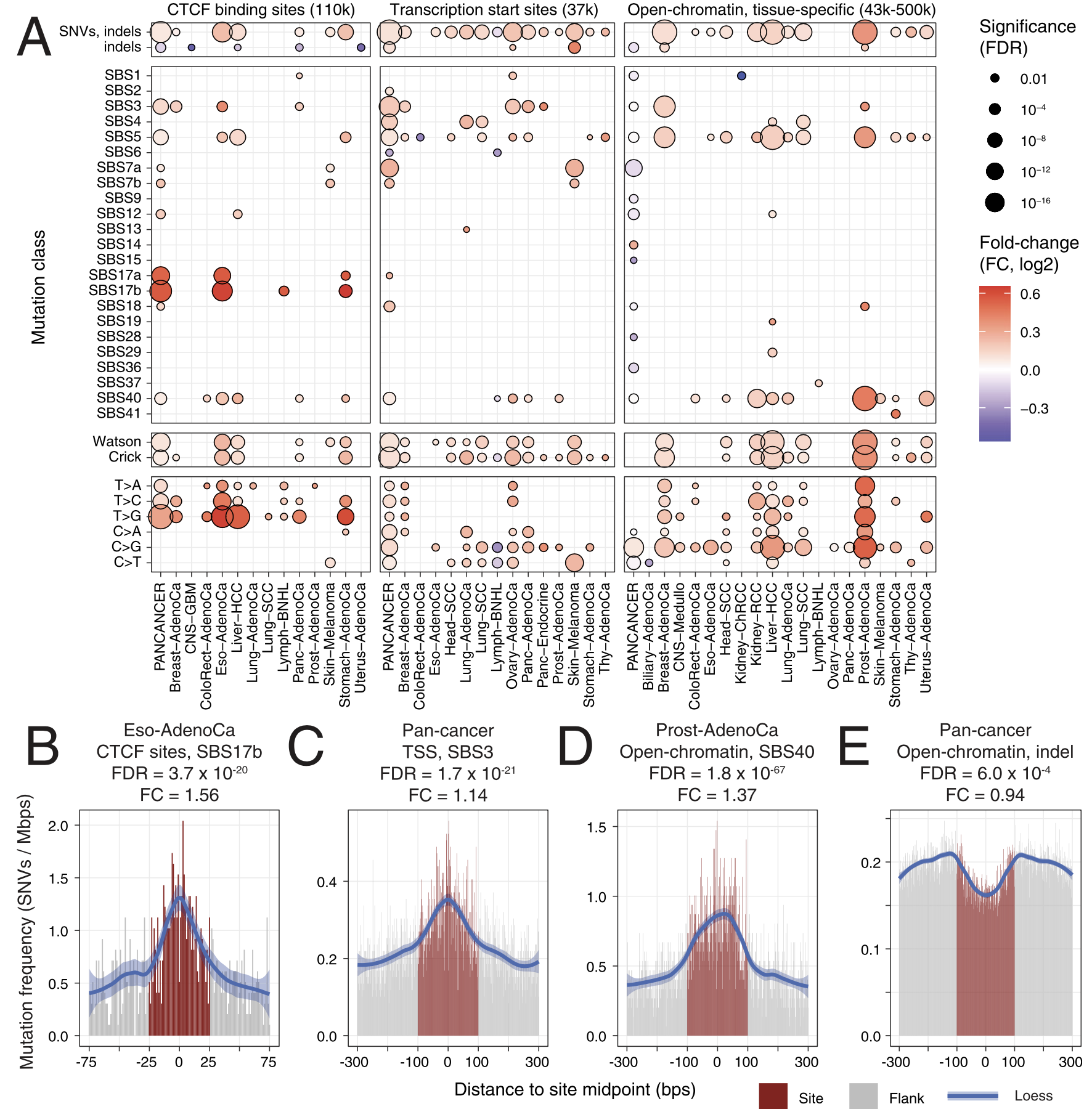

For passenger mutations, we recently focused on localized mutational processes acting on thousands of gene-regulatory and chromatin architectural elements of the cancer genome. We characterized the potential functional and genetic determinants of mutational processes at binding sites of the CTCF chromatin architectural factor, gene promoter elements and cancer-specific open-chromatin regions. For example, promoters of highly expressed genes and CTCF binding sites epigenetically conserved across many human tissues display the greatest extent of somatic mutagenesis. We also found that certain driver mutations in cancer genomes significantly increase the apparent activity of these mutational processes.

Functional and genetic determinants of mutation rate variability in regulatory elements of cancer genomes.

Christian A Lee*, Diala Abd-Rabbo*, Jüri Reimand.

Genome Biology 22 (1), 133 (2021)

link.

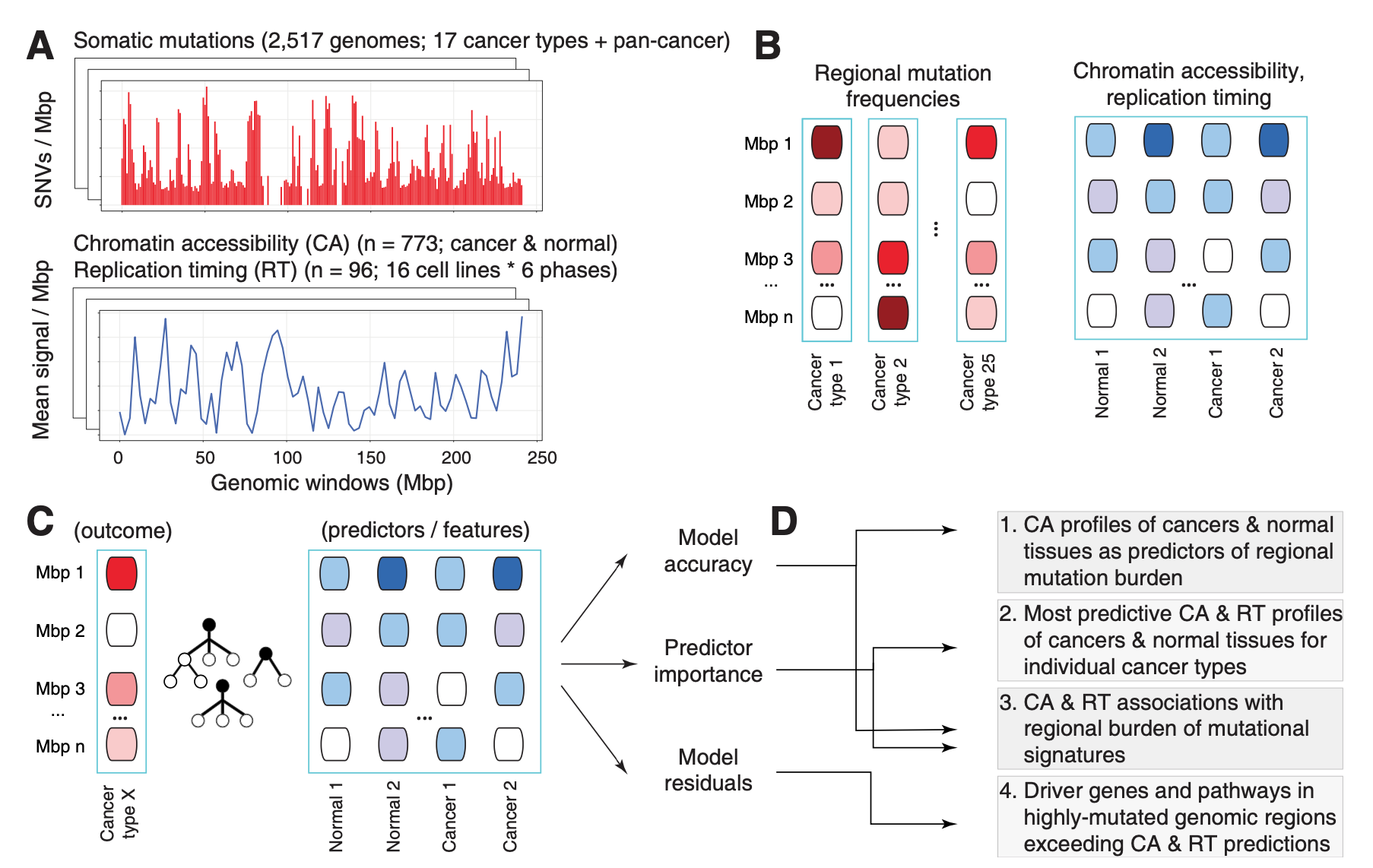

In another study of passenger mutations, we dissected mutational processes in cancer genomes and their epigenetic associations with tumor tissue of origin. Using a machine learning approach (a random forest with SHAP feature prioritisation and permutation tests) and a compendium of ~900 genome-wide epigenetic tracks of primary cancers and normal tissues, we predicted megabase-scale mutation rates in ~2400 whole cancer genomes and asked which epigenetic predictors contributed the most to somatic mutation burden and mutational signatures.

We found that the epigenomes of primary cancers, rather than those of normal tissues, are the predominant predictors of somatic mutations in most cancer types in intricate tissue-specific associations: for example, somatic mutations in breast cancer genomes were most predictable by the epigenomes of primary human breast cancers, while normal breast epigenomes were not significant predictors. This suggests that the mutational landscape of cancer genomes is more strongly determined by the cancer-specific chromatin environment that occurs after transformation of normal cells to cancer cells.

The analysis also revealed a landscape of epigenetic associations with mutational processes, where certain signatures were more strongly driven by the epigenomes, especially carcinogenic signatures and signatures of unknown origin.

Lastly, we demonstrated that the epigenome-informed models can point out regions with known and putative driver mutations, as epigenomes explain a large fraction of the genomic variation, thus any regions with over-represented mutations exceeding these machine learning driven predictors.

Chromatin accessibility of primary human cancers ties regional mutational processes and signatures with tissues of origin.

Oliver Ocsenas, Jüri Reimand.

PLOS Computational Biology Aug 10;18(8):e1010393 (2022).

link

Multi-omics data integration

High-throughput omics techniques allow researchers to profile all molecules in cell in a single experiments. Next-generation sequencing, proteomics and other technologies enable the profiling of different types of molecules, such as DNA mutations, epigenetic modifications, transcript (RNA) and protein expression levels, post-translational modifications of proteins, etc. Researchers often use a combination of these techniques to profile biological samples or even single cells. However, the analysis of resulting datasets is a complex challenge since the various technologies measure different aspects of cellular logic and the datasets are not directly comparable.

Our lab develops computational tools for multi-omics data integration. We use statistical techniques such as data fusion to jointly analyze multi-omics datasets and prioritize genes, proteins and other features through these datasets. A central tenet of such multi-omics data integration is that important molecular signals detected in multiple datasets should converge to biological pathways and processes.

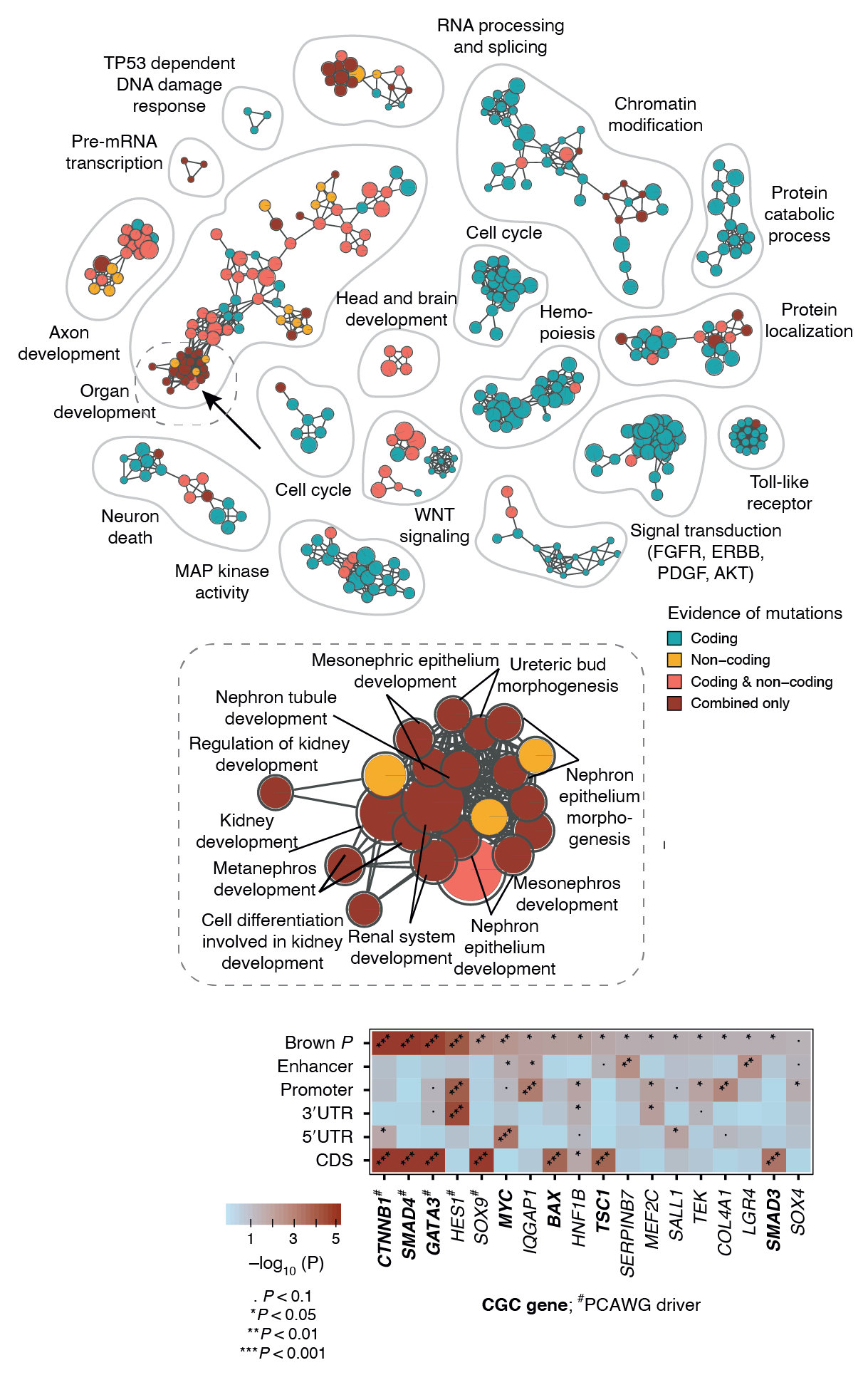

Our recently developed method ActivePathways combines multiple omics datasets representing either same omics type (e.g., RNA-seq) or multiple types (e.g., RNA-seq and proteomics). ActivePathways prioritizes genes and/or proteins based on their significance in individual datasets, giving a higher score to those genes/proteins that are standing out in multiple datasets. Pathway enrichment analysis of prioritized genes reveals pathways and processes characteristic of these genes, and also shows which of the input datasets contributes to the discovery of each pathway. These complex analyses are often best visualized as enrichment maps. Enrichment maps are network-based visualizations showing groups of similar pathways as subnetworks that are colored by the type of multi-omics evidence underlying the pathways.

Integrative pathway enrichment analysis of multivariate omics data.

Marta Paczkowska*, Jonathan Barenboim*, Nardnisa Sintupisut, Natalie S Fox, Helen Zhu, Diala Abd-Rabbo, Miles W Mee, Paul C Boutros, PCAWG Drivers and Functional Interpretation Working Group, PCAWG Consortium, Jüri Reimand.

Nature Communications 11 (1), 735 (2021)

link.

In the example below, we jointly analyzed whole-genome sequencing data of human cancers in the PCAWG project and integrated protein-coding and non-coding mutations in potential driver genes. At the top, the enrichment map shows biological processes and pathways with frequent mutations. Each node is an enriched pathway and these are organized into subnetworks such that pathways with many shared genes are linked by edges. Each node (i.e., pathway) is colored based on the evidence, that is, whether it was mostly identified due to protein-coding mutations or non-coding mutations in respective genes or their regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers). In the middle, a specific subnetwork corresponding to developmental processes is shown in detail. At the bottom, genes of one specific process (kidney development) are shown in the context of omics evidence supporting the pathway enrichment.

We published a comprehensive protocol paper on pathway enrichment analysis of omics datasets in collaboration with Gary Bader’s lab (University of Toronto). The paper includes a literature review of pathway analysis of omics data, best practices and current challenges, as well as step-by-step workflows for pathway enrichment analysis and data visualization.

Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g:Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap.

Jüri Reimand*, Ruth Isserlin*, Veronique Voisin, Mike Kucera, Christian Tannus-Lopes, Asha Rostamianfar, Lina Wadi, Mona Meyer, Jeff Wong, Changjiang Xu, Daniele Merico & Gary D. Bader.

Nature Protocols 14, 482-517 (2019)

link.

Biomarker & target discovery

Large high-throughput datasets of many cancer types are now available with increasingly detailed clinical and lifestyle information of patients. These datasets enable two major translation challenges of cancer research that have potential to improve patients’ journeys with cancer.

First, we need to identify genes and pathways that are potential therapy targets, that is, genes that encode dependencies for the wellfare of cancer cells and that can be ultimately used to develop drugs to treat cancer. Computational identification of these potential therapy targets is only the first step that needs to be followed by thorough experimental characterization of these targets in cell cultures and animal models.

Second, we need to identify biomarkers, that is, molecular signals in tumors that represent certain disease subtypes, high-risk cancers, or cancers responding to a particular therapy. These biomarkers are called diagnostic, prognostic and predictive markers, respectively. Reliable biomarkers allow us to predict the characteristics of a given tumor and therefore develop personalized oncological approaches to each individual patient based on the genetic and molecular makeup of their tumor. Biomarker discovery is often a machine learning exercise that uses certain datasets for model training and testing and completely separate datasets for model validation.

In our recent work, we set out to discover potential cancer biomarkers and target genes in the non-coding genome among a class of genes called long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). There are thousands of non-coding RNAs in the human genome and many of these are expressed in cancer cells, however the vast majority of these remain uncharacterized.

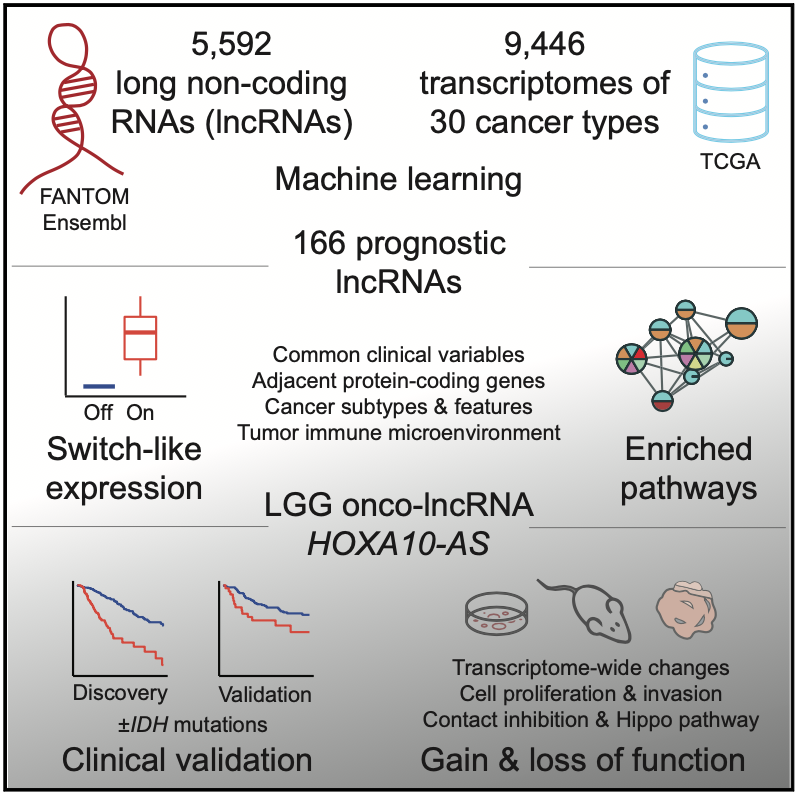

We used a systematic machine learning approach to identify individual non-coding RNA genes whose expression was prognostic (that is, indicative of patient survival time). We studied ~30 cancer types and 10,000 cancer samples of the TCGA PanCanAtlas project using elastic net models. This analysis revealed a catalogue of 166 high-confidence lncRNAs with prognostic biomarker properties in cancers. Interestingly, many of these lncRNAs showed switch-like expression and were often highly expressed in high-risk cancers and completely silent in low-risk cancers. There were numerous associations with molecular subtypes and hallmark cancer pathway activities suggesting that the lncRNAs capture patient risk and tumor heterogeneity.

We focused on one particular lncRNA HOXA10-AS that showed a strong prognostic signal in brain cancer (low grade glioma) and was associated with the expression of neurodevelopmental genes in patient transcriptomes. Our validation efforts indicated this lncRNA as a potential drug target as well as an informative prognostic biomarker, underlining the potential of this integrative analysis.

On the one hand, the lncRNA HOXA10-AS appears as a potent onco-lncRNA and a potential drug target since its experimental inhibition using shRNAs reduces cancer cell growth while it over-expression increases cancer cell invasion based on our experiments in cell lines, xenografts and organoids. Thus, advanced brain cancer cells may depend on this lncRNA for growth and survival.

On the other hand, the lncRNA expression helps identify high-risk tumors that associate with poor patient prognosis, as observed in the cohort of brain cancers from TCGA we used for model training, as well as another patient cohort from our collaborators at the Huashan Hospital that we used for model validation.

Pan-cancer analysis of non-coding transcripts reveals the prognostic onco-lncRNA HOXA10-AS in gliomas.

Keren Isaev*, Lingyan Jiang*, Shuai Wu*, Christian A. Lee, Valérie Watters, Victoire Fort, Ricky Tsai, Fiona J. Coutinho, Samer M.I. Hussein, Jie Zhang, Jinsong Wu, Peter B. Dirks, Daniel Schramek*, Jüri Reimand*.

Cell Reports 37 (3), 109873 (2021).

link.